-

The opera dramatizes the relationship between two women who found each other in the midst of a complicated world - and especially a world where men in positions of power have told them, one way or another, that their minds and bodies have little value. One of these women is Eleanor Roosevelt, who is about to become First Lady of the United States. The other is Lorena Hickok (or Hick, as everyone seems to call her), a feisty journalist assigned to introduce Eleanor Roosevelt to the world. Fantastically told through metaphysical poetry, fragments of newspaper accounts, intimate letters and Depression-era ballads, the opera retells these women’s stories as a classic love triangle – between Eleanor, Hick and a composite character known simply as The Outside World. Ultimately, the impossible love Eleanor and Hick share for this Outside World – an especially troubled world that desperately needs them – threatens to pull the two apart.

Instrumentation & Technical Requirements

Solo Saxophones (PV) - baritone, tenor, alto and soprano saxophones

Strings

Piano / Synthesizer

Electronics / Pre-recorded Audio - multitracked recordings of Present Voice (all saxophones), Outside World, Eleanor, and Upright Piano

Playback through onstage speakers, which should be placed inside a large, vintage radio.

Running Time

ca.90 minutes (without intermission)

Program Note

In the most obvious sense, The Impossible She is a love story rooted in the historical record – a story of two women who find one another in the midst of a world, especially a world of men in positions of power, that tells them that their minds and bodies have little value. One of those women is, of course, Eleanor Roosevelt and she’s about to become First Lady of the United States. The other is Lorena Hickok, or Hick, as everyone seems to call her, and she’s the feisty and impressively successful journalist assigned to introduce her to the world – an outside world in turmoil and distress. This Outside World is the third character in the opera – sometimes cruel and dismissive, sometimes sympathetic and adoring – a shape-shifting figure who intrudes upon yet also fuels the two women’s relationship.

Beyond offering the faint outlines of this mostly true story, however, I’ve conceived of this opera as an exploration of how we imagine ourselves in the past – both the real and fanciful past – in the hope that it tells us just a little something about our dizzying present. With this in mind, the fourth main “character” isn’t a singer or actor at all, but rather an unspeaking, omnipresent saxophonist I’ve simply called Present Voice. Like us, this figure imagines themselves in a distant past that was never theirs, showing up in situations where they don’t belong, in which the actual details of history are spotty and require large imaginative leaps. Present Voice doesn’t have quite enough information, yet still summons the spirits of these two forebears, not exactly as they were but as we might imagine them – much like we do when we open a book* or listen to a recording.

The libretto, in keeping with this approach, is a reimagination of fragments from the past, as encountered and reimagined by a present voice – by me, you and us. It’s a meditation on a relationship through the various lenses we have to see into Eleanor and Hick’s world – newspaper accounts, long-secret intimate letters, personal recollections and Depression-Era ballads, complemented by three English poems from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that the two women “exchange” in song. Like the opera itself, these poems represent a semi-fanciful leap into the past; we know that Eleanor and Hick read poetry to one another from The Oxford Book of English Verse, but which poems is entirely speculative. I have chosen those that resonate most with my sense of how we might summon these spirits and their time together.

Speculation is part of playfulness, and playfulness is part of imagining worlds we have never visited. That has been my goal here. To playfully fill in the lines not just of what we know about these two women and the moment in which they endeavored to love each other, but how we know and experience it. And so, as aspiration at least, how we might see our own loves and longings played out in lives not our own.

-

Over the course of three successive evenings, each one its own act, a rather queer and rather neurotic household has a political calamity visited upon it. This is the musical and narrative shape my collaborators and I arrived at from our original idea of staging three short plays by Gertrude Stein—Photograph, Captain Walter Arnold, and The Psychology of Nations—as a chamber opera set in a single domestic interior. The high-strung couple, avatars of Stein (as a low mezzo-soprano) and Alice Toklas (as a high tenor), move with their wacky (soprano) cousin-cum-maid and occasional guests—the string quartet—through a parlor play, a shopping expedition and an erotic adventure, oscillating between high jinks and boredom.

Taking my cue from the playfulness of Stein’s own language, nothing in the opera ever quite stays in its place, and most everything circles back on itself, textually and musically: the sewing machine sings, the phonograph won’t stop, the radio becomes deranged by disco. It’s all a nervous kind of enjoyment, not pure frippery, but serious play. That is until the presidential election party on the final evening, when the radio brings news of a cataclysm, and they must reckon their pleasures against history’s sudden unfolding.

Libretto by Adam Frank with Daniel Thomas Davis

Running Time

ca. 120 minutes

Cast & Ensemble

V – mezzo-soprano; more or less Gertrude Stein; a writer and impresario, the “voice of the household”

ME – tenor; more or less Alice Toklas; V’s loving, anxious spouse; performed in drag or non-binary attire

THREE – soprano; a sassy cousin who keeps house for V & ME

WE – cabaret-style singing and speaking role; also plays keyboards** a narrator and radio announcer

FRIENDS/GUESTS – who just happen to play:

Violin 1 (doubles hi-hat cymbal in Act 3)

Violin 2Viola (doubles kick bass drum in Act 3)

Cello (cello stand required for onstage movement)

Piano

Technical Requirements

**2 KEYBOARDS – preferably played by WE in Act 3; set up as twin-tiered, pop synths

Keyboard A = at pitchPatch #1: Vintage Disco Synth (at pitch) Patch #3: Electric Harpsichord (at pitch)

Keyboard B = tuned 1⁄4 tone down Patch #2: Vintage Disco Synth (1⁄4 tone flat) Patch #4: Electric Harpsichord (1⁄4 tone flat)

*** AUDIO PLAYBACK For pre-recorded, multi-tracked “phonograph” recordings in Act 1: Scene 1 and Scene 4.

Synopsis

ACT 1

An entertaining evening at home with a group a friends. V, ME, and THREE try to stage a parlor play called “Photograph,” which centers on a photograph of an immigrant family on the verge of separation.

PRELUDE: V, ME, and THREE prepare to receive guests, each in their own daydream. A group of string-playing friends wanders onstage for the evening’s entertainment.

SCENE 1: The parlor play begins with a jaunty song. When the doorbell rings, V and ME perform a brief dance together. THREE answers the door to receive an egg delivery. The parlor play recommences, accompanied now by a record on the phonograph.

SCENE 2: The play continues with a scene about a boat to America performed by THREE with puppets and shadows.

SCENE 3: Still performing, V and ME look at the photograph of a family on the verge of separation. Over the course of the scene a single photograph multiplies.

SCENE 4: V, ME & THREE continue the parlor play but then abandon it entirely. In an effort to lighten the mood, they play a guessing game on the phonograph. Nobody wins. The guests go home and the household retires to bed.

DIVERTISSEMENT

Our narrator, WE, performs a short diversion: “A Curtain Raiser.”

ACT 2

A seemingly quiet evening at home. The same interior, now with a sewing machine and dress-form.

SCENE 1: THREE works at the sewing machine, while ME and V argue about ME’s recent shopping expedition. After playing dress-up with the new purchases, the scene takes an erotic turn.

SCENE 2: V and ME get it on. THREE tries, but not too hard, to make herself scarce.

INTERMISSION

ACT 3

On a subsequent evening, our household hosts a presidential election-night party. The same parlor, now featuring a giant radio console. A RADIO VOICE (WE), accompanied by several musicians, announces the news from inside the radio.

PRELUDE: A guest pianist plays along with dance music from the radio, but is pungently off. THREE serves a plate of brownies. ME eventually changes the station.

SCENE 1: The radio comes to life while the partygoers listen and respond. Newsy review before the election returns.

INTERLUDE: THREE turns the dial and offers gin to the partygoers when dance music comes from the radio again.

SCENE 2: ME rushes in and hands out newspapers to the partygoers. THREE keeps fiddling with the radio dial while ME shares disturbing news. As the party and the election start to come off the rails, ME panics, V narrates events with punk-ish rage, and THREE repeatedly tries to change the subject and the radio station.

SCENE 3: The radio becomes deranged as the news gets worse. An eerie calm, then the machine takes control. Breaking out of the radio console, WE inflicts a mortal wound on ME, then exits.

SCENE 4: A few hours later. V and THREE, now repentant, don funeral veils and attend to the dying ME. Lament. Resurrection.

-

When I first started work on this collaboration, I received a voluminous amount of poetry and prose – a loose bundle of new work by seven of the finest writers currently working in and around the Southern voices of American literature. As I slowly made my way through these stories and stanzas, I began to understand something I had already intuited – these writers all know one another. And one way or another, the people that inhabit their writings all seem to know one another, too. Their voices, characters, and almost-forgotten-but-now-remembered friends and family – they all seemed to live in proximity to one another. With this thought in mind, Family Secrets: Kith and Kin began to emerge as a series of loosely related portraits – from small faded snapshots to larger-scale paintings, with even a comical caricature or two.

As I began sketching out these portraits, two shapeshifting figures gradually came into focus: the first, a Mother/Daughter character, whose singing voice would serve as the piece’s laughing, lamenting, testifying and atoning protagonist; and the second, a Friend/Neighbor, whose speaking, yarn-telling voice would be the work’s narrative engine. The resulting musical drama soon took on a fundamentally hybrid form – an opera on top of chamber music, or a song cycle inside a monodrama. Now, after several wonderfully different productions, I sometimes just call it a chamber opera, but I’m still not entirely sure what it is. And ultimately, I hope that ambiguity might be felt as part of the work’s underlying message – we live, love and die in close relation to one another, but the textures of those relationships shift over time and resist easy definition.

Like the characters onstage, the instrumental ensemble here speaks with an accent, most pronouncedly with the twangy banjo that lurks and lilts beneath the score’s surface, but also in striding piano riffs and high-lonesome fiddle solos. And like the piece’s dramatic structure, the ensemble also seems to be several things all at once – a motley, front-porch pick-up band but also a reimagined Baroque orchestra that took a wrong turn somewhere across three centuries and two continents. For reasons I still can’t explain, when I was writing for this ensemble, the poignant intimacy of the Bach cantatas always seemed to be in my mind’s ear, perhaps most obviously in Randall Kenan’s bloodstained parable of the Great Migration in Scene 5: “Chinaberry Tree,” but also in the breathlessly long melodic lines that meander through Allan Gurganus’ full-throated epilogue and Frances Mayes’ brooding “Net.”

Uniting the many disparate elements that run through the work, there’s one voice that has been the guiding spirit here – a many-hued voice I first heard and admired a few weeks after leaving North Carolina in the late nineteen-nineties and which belongs to someone who has since become a cherished collaborator and friend. To be sure, the ability to write for an artist like Andrea Moore is one of the greatest gifts I can be given as a composer, and working with her closely on this project has been a real joy. On behalf of all of us who have collaborated on this endeavor over the years, I thank her for inviting us to create a world together – and for rendering us all kith and kin.

Libretto --- Allan Gurganus, Randall Kenan, Lee Smith, Frances Mayes, Daniel Wallace, Michael Malone and Jeffery Beam

Concept --- Daniel Thomas Davis & Andrea Edith Moore

Commissioned for Andrea Edith Moore with support from the North Carolina Arts Council, Orange County Arts Commission, University of North Carolina, Kenan Foundation and a network of individual donors

Premiere production by North Carolina Opera

Duration

ca. 65 minutes

CastMother/Daughter

Friend/Neighbor

Instrumentation

Oboe/English Horn • Violin • Cello • Banjo • Piano • Pre-recorded Audio

-

A Micro-Opera in Two Acts and Two Minutes

Voice • Fixed Media Playback

Duration

ca. 2 minutes

-

Instrumentation

Flute/Piccolo • Clarinet • Bassoon • Piano • Violin • Viola •. Cello • Bass

Duration

ca. 14 minutes

It’s my hope that the title, Hard Spring, invites overlapping meanings. In the most basic sense, it might call to mind a difficult season, perhaps a bit like the one that yielded some of the original ideas for the first and last movements – secret music I’d fooled myself into thinking would never leave the safe confines of my phone’s audio-memo folder or the strings of the hurdy gurdy that lives in my studio. At the same time, I’ve also imagined the piece as an extended riff on the act of springing – or, better yet, emerging. Each of these three movements strike me as somehow about the unending process of becoming or unfolding: blocks of sound emerging from echoes and shadows, tunes surfacing in unlikely textures, and a constantly pulsating joy springing between unmatched colors.

And speaking of joy: Hard Spring is part of my series of recent works that, conspicuously or implicitly, aims to channel an often-shifting, always-becoming, never-quite-attainable sense of queer joy. In this piece’s intimate orchestration, I’ve embraced the delicate, marginal, and attenuated places within the instruments, which feel to me something akin to wordless voices among a small circle of queer fellow travelers – both from the historical past and from my own present – all of whom have fueled my own sense of becoming and belonging.

-

Instrumentation

Flute/Piccolo • Eb Clarinet/Bass Clarinet • Violin • Cello

Duration

ca. 18 minutes

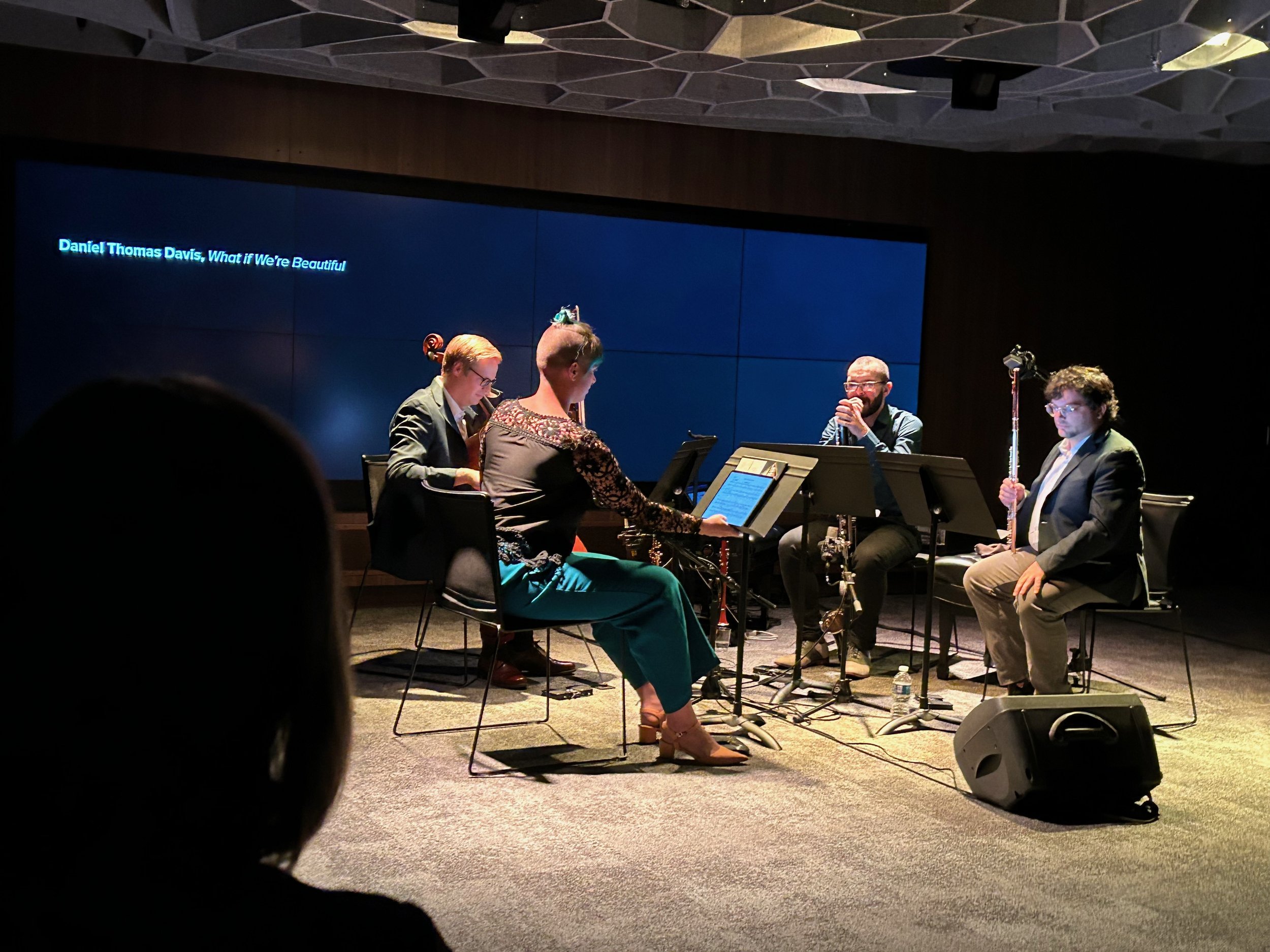

Program Note

What if We’re Beautiful is an experiment in musical gift-craft. I don’t knit or crochet, but even so, I imagine these movements as something akin to handknit musical objects woven from modest sonic threads, each made with a particular recipient in mind. And although there are countless fine examples of composers making imagistic portraits or reflective dedications, I’ve aimed for something a little different here – each piece feels to be less portraiture of any particular person and more as an opportunity to make something enjoyable for a few folks I hold very dear. In doing so, it’s my hope that others who hear and play this piece – including my friends in Hub New Music – also find something meaningful, too.

To be sure, the gifts offered in this piece are themselves the refraction of the countless and intangible gifts of queer (and queer-adjacent) friendship and joy I have received from the band of fellow travelers acknowledged in these movement titles. And although I didn’t immediately set out to write a piece about queer joy, that’s basically what happened here anyway; as the piece came together, it became increasingly clear to me that it’s also an appreciation of the boisterous, delicate, wacky, campy, and sorrowful joy that we can offer to one another.

-

Instrumentation

Flute • Clarinet/Bass Clarinet • Violin • Cello • Piano/Synthesizer

Duration

ca. 16 minutes

Program Note

Growing up in the rural American South, I’d occasionally hear the phrase “real country” as a way of identifying people – sometimes even my people, sometimes even me. It didn’t so much as describe a person’s profession or place of residence but rather something more qualitative – a characteristic walk or stride, a peculiar taste in food or conversation, and above all else, a richly accented voice thick with dialect and diphthong. It was something inside the body that just happened to make its way out somehow.

It’s that something within the voice that prompted me to write Real Country. Although I’ve titled each movement after a particular old-time country or gospel singer, I’m not really aiming to imitate any of them here – nor do I lay claim to anything resembling an “authentic” or “real” country style. First and foremost, this piece is a purely instrumental response, prompted by my listening over and over again, to a handful of special singers, all the while wondering and imagining – what sort of music do these voices invite? What idiosyncrasies and ornaments might I excavate from these old, strange and weird worlds? And how might I reimagine them in my own musical landscape?

There are, to be sure, a number of tunes here, too – some traditional ballads, some my own creation, others that fall in between. Some might recall the high-lonesome lament of the Appalachian murder ballad, others the ecstatic hollering of low-church gospel, and yet others the syrupy lilt of old-time country’s jilted lovers. Throughout it all, I think of these melodies as places to wander – pathways and byways mostly – each one traveled and populated by the peculiar, sputtering, plain and joyful voices of this other country – my country.

-

Instrumentation

String Quartet • Marimba • Piano/ Synthesizer/Hammond Organ

Duration

ca. 16 min.

-

Instrumentation

Soprano • Flute/Piccolo • Clarinet/Bass Clarinet • Violin • Cello • Piano

Duration

ca. 15 minutes

Program Note

Like a path worn by many centuries of travel, the ancient poem "phainetai moi" has hosted many wanderers. Over the past twenty-five hundred years, this short fragment by the Greek poet Sappho (ca. 600 BCE) has captivated generations of other poets and commentators – prompting a wild gamut of translations and adaptations. For some, the text signaled the emergence of a lyrical strain in Western art that would extend to the modern era; for others, it offered an intoxicating utterance of unfettered romantic freedom. For others still, it provided an intriguing catalog of out-of-body experiences.

Fascinated by the ways in which this short text has had such a long life, I’ve based each of the four songs in Follow Her Voice on a different translation or reworking of "phainetai moi" – some far closer to the original text than others. “Wand’ring Fires,” the first song of the set, uses a rhyming translation attributed to the seventeenth-century English spy, playwright and poet Aphra Behn. Jumping forward more than three centuries, the subsequent movement then features an original poem (“That Man,” 2010) by the American poet Maureen McLane, written in response to Sappho’s fragment. In the third song, “Thin Flowing Flame,” I’ve set Catullus’s Latin adaptation of the Greek original (ca. 50 BCE), in which the Roman poet reworks the text as a hymn to his mistress. Finally, in “Starless Light,” the fourth song of the set, I employ Lord Byron’s tumultuous rendition (ca. 1820) of Catullus’s poem – a kind of translation of a translation of a translation.

-

Instrumentation

Voice • 3 Flutes • Violin • Bass• Percussion • Electric Harpsichord

Duration

ca. 15 minutes

Sung texts freely adapted, by the composer, from the “Book of the Faiyum” (ca. 100 BCE) – a Greco-Egyptian papyrus from the Faiyum Oasis.

I. Sunrise on Crocodilopolis

II. Naos of Neith, by Her Sacred Tree

III. Island of Fire

IV. Menmehdet: The Fighting Place

V. Dwelling Place

Program Note

Throughout my engagement with the ancient Egyptian “Book of the Faiyum,” I was struck by the ways in which a text so old, strange and seemingly unfamiliar might nonetheless ignite the imagination of a twenty-first-century viewer and listener. My musical response is one in which contemporary sounds resonate alongside intimations of other, older worlds – and, I hope, one in which ancient voices might somehow speak to life in the present. Or to put it more concretely, I’ve envisioned a musical landscape in which glimpses of Coptic or Byzantine chant might occasionally give way to flashes of American popular music.

Drawing on both texts from these ancient scrolls and my imagination of ancient music more generally, my new piece features an unusual ensemble of modern and not-so-modern instruments, loosely inspired by ancient musical groups. Scored for flutes, singer, strings, handheld percussion and harpsichord, the piece is divided into five movements – each one a kind of musical map of an imaginary and shifting landscape.

-

Instrumentation

Violin • Cello • Piano

Duration

ca. 16 minutes

-

Instrumentation

VERSION A: Flute/Piccolo • Clarinet • Violin • Cello • Piano

VERSION B: String Quartet • Piano

Duration

ca. 14 minutes

Program Note

As the title suggests, I’ve conceived of this piece as a set of two different types of music – short, tuneful songs and musical “visions” that are larger in scope and wider in musical reference.

In the first movement, “Visions of Shared Cities,” I think of the ensemble as a community of distinct individuals. It begins with the full ensemble interwoven around a shared melody, from which the entire piece then unfolds. Soon afterwards, a continuous common pulse underpins a musical journey that includes both lyrical conversation and a raw, blues-tinged eruption. The subsequent movements consist of two short, more intimate songs that are played one after the other. In the first,“Song of Grateful Wooing,” I’ve imagined two sets of courting couples (cello-clarinet and violin-flute), each playfully accompanied by a folk instrument (in this case, a muted piano). The second, “Song in Unison,” is a song of reconciliation, in which all join together in a single, unison melody.

-

Instrumentation

Flute/Piccolo • Clarinet • Violin • Cello • Piano

Duration

ca. 12 minutes

-

Instrumentation

Solo Violin • Flute/Alto Flute • Clarinet/Bass Clarinet • Cello • Piano • Percussion

Duration

ca. 17 minutes

-

Instrumentation

Flute • Oboe • Clarinet • Bass Clarinet • Bassoon • Horn

Duration

ca. 8 minutes

-

Instrumentation

String Orchestra

Duration

ca. 8 minutes

Program Note

Both the initial musical material and the title for A Photograph Reproduces were drawn from my opera Six.Twenty.Outrageous, which premiered in New York. Gradually unfolding in slowly pulsing and repeating phrases, this elegy for string orchestra grew out of a scene in the opera that depicts an immigrant family on the verge of separation, just before embarking upon an uncertain, transatlantic journey.

Commissioned to mark the 75th anniversary of the Marshall Plan.

First performance by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

-

Instrumentation

3 Flutes (2nd & 3rd double Piccolo) • 2 Oboes (2nd doubles English Horn) • 2 Clarinets • 2 Bassoons • 4 Horns • 2 Trumpets • 3 Trombones • Tuba • Timpani • 3 Percussion • Harp • Piano / Celesta (1 Player) • Strings

Duration

ca. 18 minutes

Program Note

As the title suggests, I’ve conceived of this piece as a set of two different types of music – short, tuneful songs and musical “visions” that are larger in scope and wider in musical reference. In the first movement, “Common Visions,” I think of the orchestra as a community of distinct individuals in conversation with one another. It begins with the woodwinds interwoven around a shared melody, from which the entire piece then unfolds. Soon afterwards, a continuous common pulse underpins a musical journey that includes both lyrical dialogue and a raw eruption of the blues.

The second and third movements are short, more intimate songs. In the second movement, “Song of Grateful Wooing,” I’ve imagined sets of courting couples (trumpet-clarinet and bassoon-tuba, for example), each playfully accompanied by a combination of mallet percussion, piano and pizzicato strings. The third, “Song in Unison,” is a song of reconciliation, in which all join together in a single, unison melody that is introduced by two piccolos in their lowest register.

-

Instrumentation

Solo Cello • Oboe/English Horn • Clarinet • Bassoon • Piano • Strings

Duration

ca. 28 minutes

Program Note

I imagine this piece as a kind of instrumental opera, in which the solo cello assumes the lead role amidst a cast of supporting characters – i.e. the eight other players. In the first movement,“Prologue,” various combinations of the ensemble serve as a Greek Chorus that precedes the main drama of the work.At the piece’s beginning, the solo cellist acts as an accompanist to this chorus. Gradually, as the movement unfolds, the cello emerges as the soloist, culminating in a cadenza or “soliloquy” at the end of the first movement. In the episodic second movement,

“Act One,” I envision a series of short, unfolding arias compacted into a span of six minutes – culminating in a melodic passage full of nostalgic associations.The third and shortest movement,“Dances and Interludes” is a light and casual jaunt featuring pizzicato cello, double bass, and bassoon. I think of it as a dramatic foil between the weightier second and fourth movements.

The fourth movement, “Act Two,” is the work’s core. Here, an increasingly fraught and virtuosic cello solo is underpinned by call-and-response gestures between the accompanying strings and woodwinds. Fast and unrelenting, the movement builds through a series of climaxes, with an enflamed cadenza halfway through the movement. Before the final and most violent crescendo, a lone bassoon recalls a frail and fleeting fragment of Act One’s nostalgic “aria.” In the fifth and last movement, “Epilogue and Processional,” the cello takes on a meditative and lyrical character – with a slow, simple ostinato rolling forward in the piano and bass. I imagine this movement as both a love scene and ritualistic procession.

-

Instrumentation

Solo Violin • Flute/Alto Flute • Clarinet • Piano • Percussion • Strings

Duration

ca. 16 minutes

Program Note

My initial inspiration and a host of subsequent ideas for this piece all stemmed from a single sentence in a short story by Willa Cather: “It never really died, then – the soul which can suffer so excruciatingly and so interminably; it withers to the outward eye only; like a strange moss which can lie on a dusty shelf half a century and yet, if placed in water, grows green again.” Both a narrative thread and a broad metaphor, the idea of this dry, lifeless object returning to life upon the presence of water served as an organizing principle for the piece, which is divided into three distinct but continuous movements:

In “Part 1: The outward eye,” the lone, nearly unaccompanied violin introduces short fragments of plaintive melodies – all in the lower reaches of the instrument – never quite managing to expand them into a longer, continuous tune. In “Part 2: Like a strange moss grown green,” the ensemble finally enters with a series of chorales, above which the solo violin emerges with increasing virtuosity, height, and abandon. In “Part 3: Past what happy islands,” the underlying elements of gospel, country, and blues that had tinged the previous movements come to the fore with a more unabashed, dance-like spirit. Ultimately, primal harmonies and constant, raw modulations erupt into an extroverted, sustained song.

Throughout the work, I’ve thought of the violin not so much as an instrumental soloist but as a human voice – an operatic heroine from which the spotlight never wanders. In this scenario, the ensemble forms a constantly changing landscape that impacts and informs the central figure but only towards the end becomes a set of supporting characters.

-

Instrumentation

2 Flutes (2nd doubles Piccolo) • 2 Oboes (2nd doubles English Horn) • 2 Clarinets • 2 Bassoons (2nd doubles Contrabassoon) • 4 Horns • 2 Trumpets • Tuba • Percussion (1 player) • Harp • Strings

Duration

ca. 12 minutes

Program Note

For a number of years now, I've found creative inspiration in the rich tapestry of American musical traditions - sometimes discovering a vibrant newness in something very old. In particular, the massed congregational singings and early gospel music once prevalent in the American South have often captivated my musical sensibilities. Although simply mimicking this music seems problematic, exploring the expressive potential of group religious singing strikes me as particularly exciting on the large canvas of an orchestra. A complicated legacy, these singings were a participatory music that fostered deep ties of community but also had the capacity to erupt into extreme and jarring emotionalism.

After recollecting a few experiences from my childhood in the rural South and then studying various recordings of old-school singing traditions, I was drawn to the way that an individual singer relates to the rest of the group - as everyone more-or-less sings the same thing but with constant, personal inflections. Here, I sense a raw, emotional impulse that can be individual and communal - and at times both good and evil. In the first half of the piece, I imagine a sequence of different choruses, each of which appears and vanishes like a memory of something past. For these choruses, I've divided the orchestra into a series of distinct instrumental “congregations.” Each of these congregations has one or two instrumental “voices” that begin to stick out, almost uncontrollably, from the rest of the group. Ultimately, these various groups merge into an explosive passage for the entire orchestra that becomes increasingly impassioned and inflamed as the individual voices from the first sections are now consumed by a larger fervor. Afterwards, the piece closes introspectively with a lyrical epilogue.

-

Three Treble Voices

Duration

7 minutes

I’ve imagined a composition that consists of two fundamentally separate musical layers, each informing the other but each with its own distinct language and personality. In one of these musical layers, based on Hildegard’s radiant chant O virtus Sapientie (“O Wisdom’s Energy”), a flowing and twisting melody passes freely between the vocalists. At the same time, a second, slowly pulsing layer of music gradually unfolds over the duration of the piece. In this musical layer, I’ve assembled texts from Hildegard’s mysterious Lingua Ignota, an invented, secret language she devised for reasons that still remain unclear. In an allusion to Hildegard’s idea of earthy wisdom, the first half of this music features consonant- heavy, imaginary words that denote species of trees and plants, while the second half then employs the names of flying birds — wisdom soaring high above the heavens.

-

Instrumentation

Version A: Treble Voice and Electric Viol

Version B: Treble Voice and Electric Hurdy Gurdy

Version C: Treble Voice and Cello

Duration

ca. 12 minutesNote

The three texts, which were probably written by anonymous women in the late 1400s, were adapted from the Middle-English Findern Manuscript.

When I first encountered these three poems, my mind and ear turned almost immediately to one fundamental idea --- these texts were, in a particular half-millenium-old way, torch-song lyrics. With that in mind, I set about writing a set of three songs that brings together a number of recognizable elements in 20th- and 21st-century popular torch songs with the gestures, mannerisms and syntax of much earlier musical and literary practices. Here, instead of Nina Simone and piano, Dolly Parton and guitar, The Carpenters, or Donna Summer and disco synth, we have a different sort of duo, but one with clear overtones back to vernacular genres. The results, I hope, are not so much torch songs from another time or another place but rather songs from a place and time parallel to our own.

-

Instrumentation

Solo Soprano, SATB Voices, Marimba, Harp and Strings (or Organ)

Duration

ca. 17 minutes

Note

Throughout work on King David’s Songbook, I was fascinated and inspired by the cultural weight attached to psalm singing across the millennia. My decision to set texts from the 1640 Bay Psalm Book – the first booked printed in British North America – certainly raised one particular set of historical associations. Yet, ultimately, my fundamental attraction to these translations stemmed from the spare, unpolished, and sometimes downright clunky language in this oddly rhyming verse. Each seemingly simple and direct word or syllable opened up a new but strangely old world that invited musical exploration.

Beginning with the notion that the psalms have engaged both personal and communal forms of expression, I’ve synthesized specific elements of psalm traditions from various cultures into the musical fabric of the work. Not necessarily apparent as distinct references, these allusions range from medieval Ethiopian psalmody to the gospel music and shaped-note singing of 19th- and 20th century America. Meanwhile, in addition to enjoying the lovely sounds of the harp, marimba and organ, I also sense a symbolic association in these three instruments – again, something very old embodied in the new. A harp and marimba might suggest the ancient lyre and psaltery that might have accompanied a more intimate type of psalm singing. Likewise, the organ recalls the centuries-old practice of singing psalms with a simple organ accompaniment that often shadowed the voices.

I conceive of this meditative piece not as a self-standing setting of one psalm text but rather as a small collection of individual songs in which fragments of thematically related psalms form the lyrics. In the first movement, “Preface and Responsory,” I explore the role of the individual person amidst a larger collective, as proposed in the Bay Psalm Book’s preface, “By whom are they to be sung? By one man alone… or by the whole together?” The short second movement consists of two sections: the earthbound first part comprised of quickly incanted, despondent complaints and the more joyful second section which takes flight on the famous phrase “wings of a dove.” Finally, as the title describes, I imagine the third movement as a love-song, culminating with a meditation on the phrase “darkness and light.”

-

Instrumentation

Voice • Clarinet • Piano

Duration

ca. 5 minutes

-

Instrumentation

Voice • Clarinet • Piano

Duration

ca. 5 minutes

-

Instrumentation

Voice • Clarinet (or Viola) • Piano

Duration

ca. 10 minutes

Settings of poetry by Inta Miske Ezergailis

-

Instrumentation

solo cello

Duration

ca. 5 minutes

-

Instrumentation

solo piano

Duration

ca. 12 minutes

-

Instrumentation

Two Treble Instruments (Any Combination)

Duration

ca. 3 minutes

-

Instrumentation

2 Percussionists

• 2 Tambourine • 2 Woodblocks • China Cymbal (medium to small size) • 7 Almglocken • Vibraphone • Marimba

Duration

ca. 15 minutes

Program Note

This piece takes its title from several short essays by Rebecca Solnit – an unorthodox writer whose genre-defying work has continued to fuel my imagination over the past few years. In particular, I’ve found myself pondering her idea of the “blue of distance” – that impossibly blue color of the horizon as seen from afar. Not just any shade of blue, this is that special color that is only ever perceived from afar, vanishing as you approach. More than just a color, it signifies that particular sense of longing for something which can never be possessed.

When writing the first movement of this piece, I kept asking myself if I might be able to translate this evanescent blue of distance into a musical experience. But rather than try to mimic an explicitly visual image in sound, I turned Solnit’s idea into a question: what kind of music might simply vanish the longer you hear it? On the most basic level, this first movement is just that – a music that gradually fades away and dissipates over the course of a few minutes. Beginning with a unison melody played on all the instruments, it splinters in different directions as it slowly dies away.

Underpinned by a walking-speed pulse in the marimba, the second movement both alludes to the physical act of walking and to those rambling strings of thought that can accompany a good, meandering stroll. Here, I imagine a saunter through the musical imagination, in which the mind and ear wander from one seemingly unrelated idea to another. And like Solnit’s blue of distance, these musical musings also faze in and out of focus. The cumulative effect is meant as an invitation to the listener to enter into that same open-ended state of wonder that a long walk can offer. One foot always placed in front of the other as the mind moves on.

-

Instrumentation

Solo Banjo

Duration

ca. 4 minutes

-

Instrumentation

Violin • Cello

Duration

ca. 5 minutes

-

Instrumentation

Solo Piano

Duration

ca. 11 minutes

-

Instrumentation

2 Pianos

Duration

ca. 12 minutes

Program Note

This piece takes its title from several short essays by Rebecca Solnit – an unorthodox writer whose genre-defying work has continued to fuel my imagination over the past few years. In particular, I’ve found myself pondering her idea of the “blue of distance” – that impossibly blue color of the horizon as seen from afar. Not just any shade of blue, this is that special color that is only ever perceived from afar, vanishing as you approach. More than just a color, it signifies that particular sense of longing for something which can never be possessed.

When writing the first movement of this piece, I kept asking myself if I might be able to translate this evanescent blue of distance into a musical experience. But rather than try to mimic an explicitly visual image in sound, I turned Solnit’s idea into a question: what kind of music might simply vanish the longer you hear it? On the most basic level, this first movement is just that – a music that gradually fades away and dissipates over the course of a few minutes. Beginning with a unison melody played on all the instruments, it splinters in different directions as it slowly dies away.

Underpinned by a walking-speed pulse in the marimba, the second movement both alludes to the physical act of walking and to those rambling strings of thought that can accompany a good, meandering stroll. Here, I imagine a saunter through the musical imagination, in which the mind and ear wander from one seemingly unrelated idea to another. And like Solnit’s blue of distance, these musical musings also faze in and out of focus. The cumulative effect is meant as an invitation to the listener to enter into that same open-ended state of wonder that a long walk can offer. One foot always placed in front of the other as the mind moves on.

-

Note from Director Julia Haslett

PUSHED UP THE MOUNTAIN is a poetic and emotionally intimate film about plants and the people who care for them. Through the tale of the migrating rhododendron, now endangered in its native China, the film reveals how high the stakes are for all living organisms in this time of unprecedented destruction of the natural world.

Beginning in the filmaker’s godfather's garden in the Scottish Highlands, the film travels between conservationists in Scotland and China who devote their lives to the rhododendron’s survival. Patiently observed footage of conservationists at work combines with centuries-old landscape paintings and my speculative voice to create a thought-provoking film about human efforts to protect nature for and from ourselves.

-

This personal essay film tells the story of French philosopher, activist, and mystic, Simone Weil (1909-1943) -- a woman Albert Camus described as "the only great spirit of our time." On her quest to understand Simone Weil, filmmaker Julia Haslett confronts profound questions of moral responsibility both within her own family and 21st-century America. From the battlefields of the Spanish Civil War to anti-war protests in Washington DC, from intimate exchanges between the filmmaker and her older brother, who struggles with mental illness, to captivating interviews with people who knew Simone Weil, the film takes us on an unforgettable journey into the heart of what it means to be a compassionate human being.

-

Installation Score for Hurdy Gurdy, Electronics and Community Participants

Directed and Designed by Doug Fitch and Tommy Nguyen

Duration

ca. 60 minutes

-

Breath Catalogue is a collaborative work by artist/scholars Megan Nicely and Kate Elswit, and data scientist/interaction designer Ben Gimpert, together with composer Daniel Thomas Davis and violist Stephanie Griffin. The project combines choreographic methods with medical technology to externalize breath as experience. Dance artists link breathing and movement patterns in both creation and performance. Our goal is to expand the intrinsic dance connection between breath and gesture by visualizing and making audible the data obtained from the mover’s breath, and inserting this into the choreographic process to make the breath perceptible to the spectator. In the first phase of the project, we worked with prototypes of breath monitors from the San Francisco-based startup Spire. We are excited to be embarking on a second phase in collaboration with StretchSense from Auckland, using capacitance-based resistance bands.

-

Music for Piano & Dancer

Created in collaboration with Aaron Loux (dancer/choreographer)